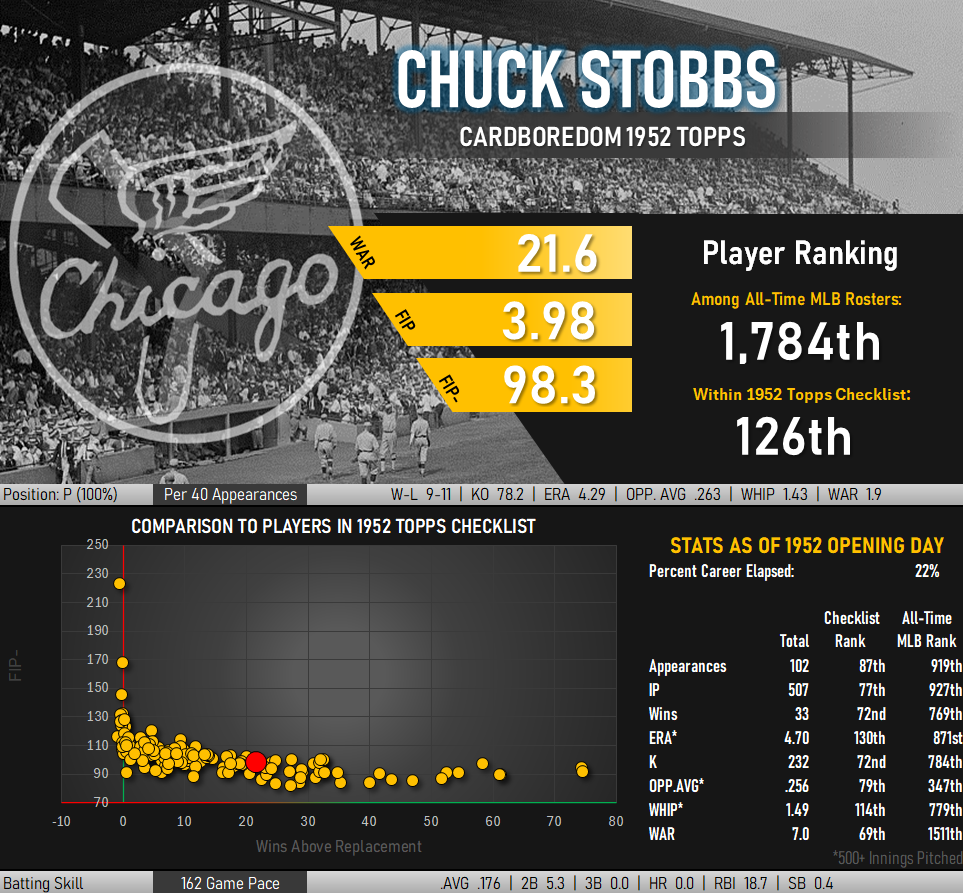

Chuck Stobbs produced average career pitching numbers across an above-average 15 seasons before retiring at only age 31. Clearly something unusual was going on when this pitcher took the mound.

Stobbs put up great numbers in multiple high school sports in Norfolk, Virginia. He was signed by the Boston Red Sox and was one of the first rookies to receive a signing bonus for doing so. Stobbs started his first major league game at age 17 and bounced around teams for a few years until he landed with the Washington Senators. Much to his chagrin, he gave up Mickey Mantle’s record 565-foot home run in his first appearance with Washington. While most people end the story at that point, it should be noted that Stobbs shut down Mantle from that point forward, giving up only singles and a .111 batting average across dozens of appearances against the Yankee slugger.

Although Stobbs struck out more batters than he walked over the course of his career, control would desert him for brief stretches. This may have been related to a vision condition that was not addressed until late in his career. In the same season that he began to keep Mickey Mantle from getting on base Stobbs threw the wildest wild pitch ever seen. He sent a pitch into the 17th row along the first base side of Griffith Park. Two years later he fell into a pitching slump that saw batters hit .380 against him for the season. None of these stories are positives at first glance and stand out for how far outside the norm they are. However, the extent to which Stobbs’ career stats bring these outliers back into the very center of normalcy (20+ career WAR) is a testament to how he played most of the time.

After Baseball

Stobbs and the Minnesota Twins went on to part ways in 1961. He coached pitchers on various minor league teams and at George Washington University before fulling retiring from the sport. Later write-ups about Stobbs describe him as a private individual who enjoyed discussing Senators baseball but not the “highlights” tied to control issues and the ocaissional home run.

“So the guy hit a home run, so what? Somebody just sent me a blank piece of paper and asked me to fill out my recollections of that homer. I sent it back blank.”

Chuck Stobbs

Stobbs passed away from an extended battle with throat cancer at age 79 in 2008.

The No-Hat Club

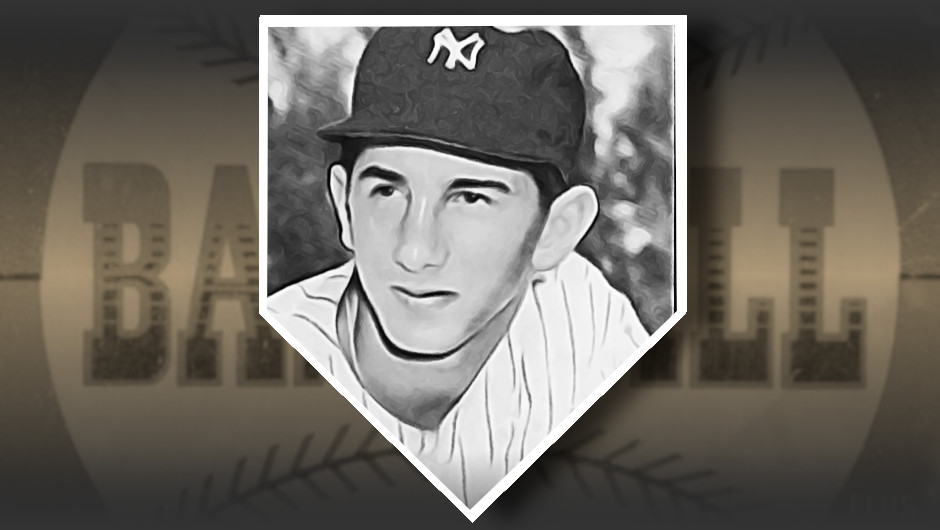

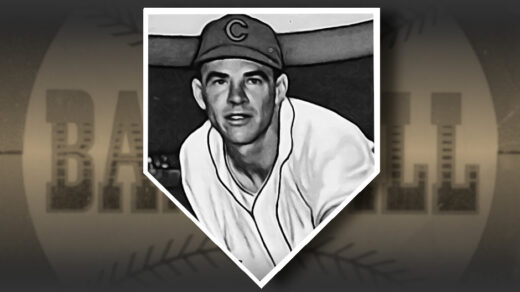

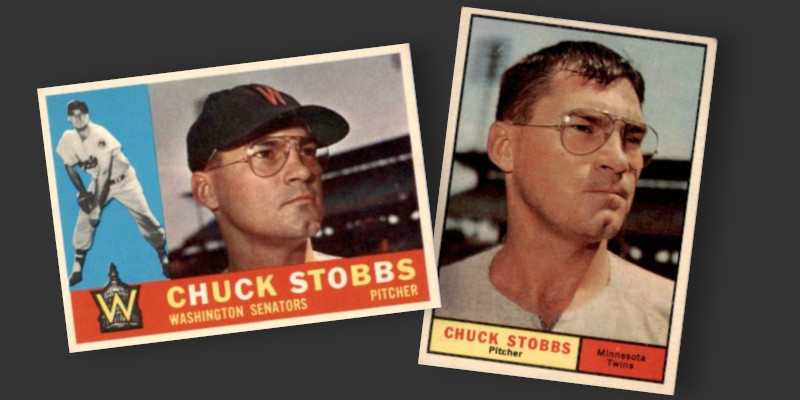

Stobbs never through a no-hitter, but he did join Topps unofficial “no-hat” club. As the card manufacturer and its contract photographers grew more experienced, they began to ask ballplayers to pose for portraits with and without their hats. This allowed Topps to quickly create a new card with a passable photo in the event that a player was traded to a new team.

The photos used for Stobbs in the 1960 and 1961 sets were taken in the same photo shoot. Stobbs was not in danger of being traded, but the team itself was considering relocating. The decision was finalized in October 1960, well beyond the end of the season. Not only did the team change cities, it was renamed the Minnesota Twins. Going into its 1961 release Topps was faced with he choice of altering a massive stack of out of date Senators photos or excluding an entire team from early runs of its baseball cards. The solution was to dive into the stack of no-hat poses taken for the prior year’s release.

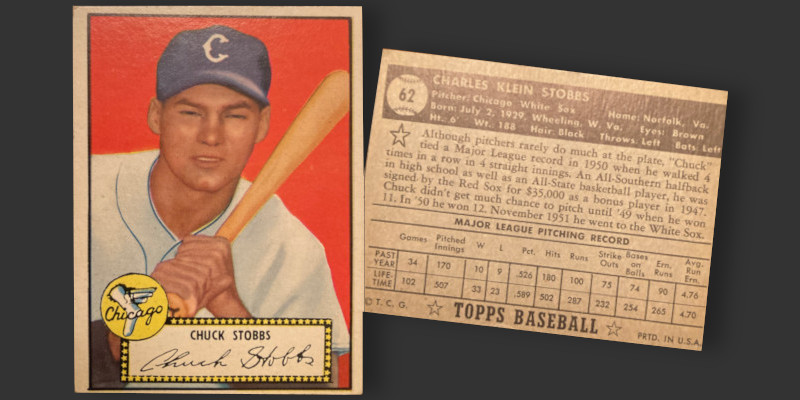

Adding Chuck to My Collection

Stobbs’ card is one of my favorites in the 1952 Topps set. So much about it encapsulates the weirdness that followed his career. First, he is pictured holding a bat. This is odd because Stobbs was a pitcher and put up the kind of offensive production that is expected from pitchers. Topps apparently thought highly of his offensive skills, depicting him diving back to first base on a pick-off attempt in its 1956 release. The card’s reverse mentions how Stobbs used his batting skills to draw four walks in just four innings of a game in 1950. It seems that the stats never tell you the entire story of Stobbs career.

Second, Stobbs looks like he is squinting pretty hard in the photo. He had trouble seeing (likely contributing to some of his rougher pitching stats) and did not get glasses until the back end of his career. The 1960s Topps cards shown earlier show him in glasses.